Magazin der Schüßler-Plan Gruppe

Ausgabe 18 | 2022 CO2

I grew up in the US. Concrete is used a lot in the States, but not as in Europe. You see it in a parking structure or an airport terminal, but much less in the buildings that you're in on a day-to-day basis. So, there is a fascination with the robustness of European construction and the ability to build something massive. That heaviness and weight almost don't exist in the US. Then in 2008 I lived in Beijing. There was an acidic smell that hung over the city, and it was always grey. Shortly before the Olympics, they shut down the factories to clear the air and hide the precarious labor on construction sites. Then the sky turned blue, and the smell disappeared. I realized that it was the smog of cement dust that had been blowing around. Later, I was teaching a design studio at the ETH in Zurich and all our students did their final models in concrete. Somehow this concrete was everywhere.

Finding out more about the cement industry, I decided to do a dissertation on how concrete became so common in Switzerland. Not looking at the architectural exceptionalism but understanding the regime of testing, norms, and industrial organizations that made concrete ever easier to use. So, it's not a love letter. It’s rather an understanding of how we got to the crisis that we're in today.

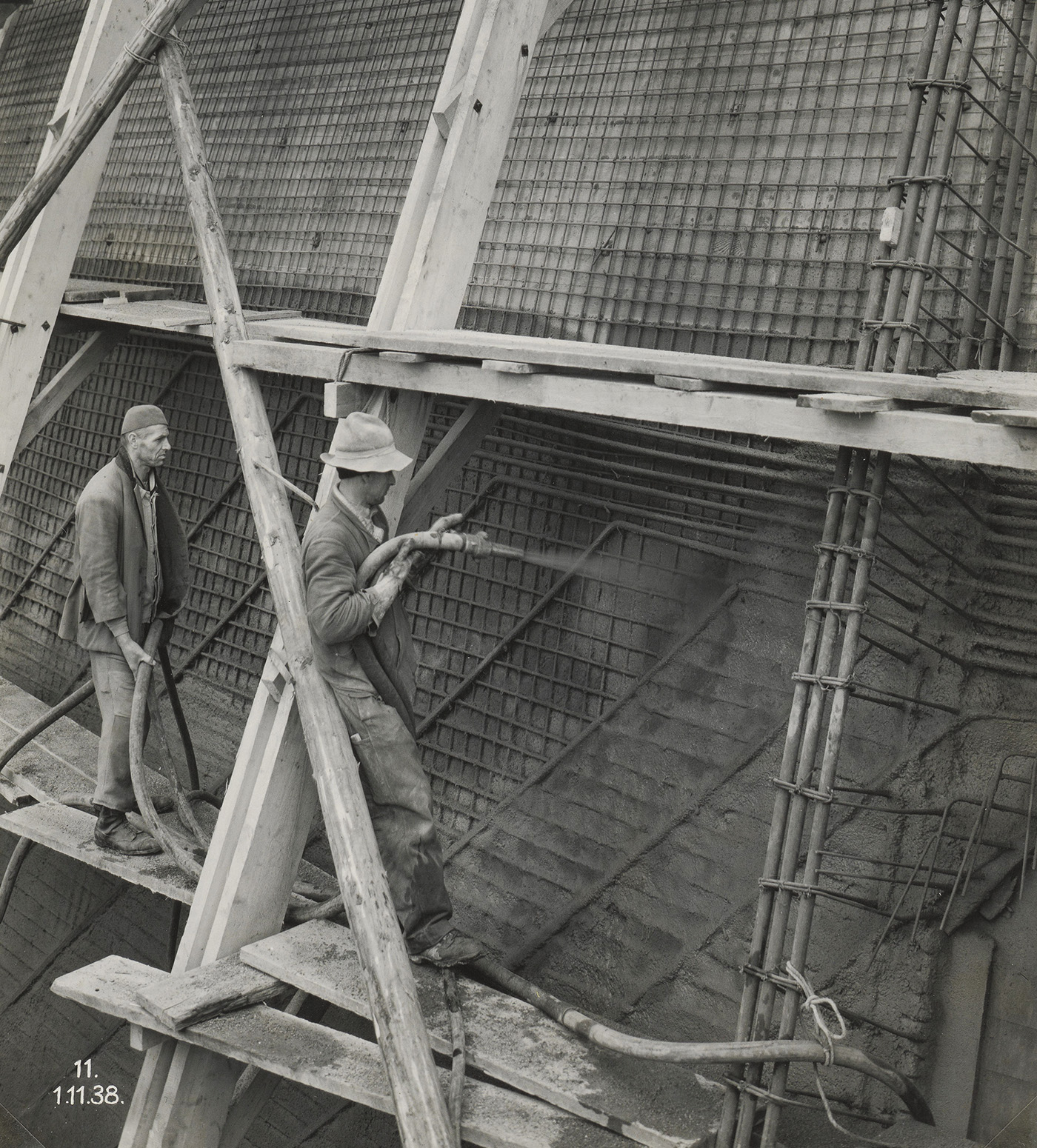

Modern (“Portland”) cement was not developed as an industrial product in Switzerland until the late 19th century, later than in France, England and Germany. In a landlocked country with a relative ‚Rohstoffarmut‘, the Swiss were reliant on imported resources for cast iron or steel construction unlike their neighbors. Modern concrete was a great opportunity, because in theory, all the ingredients were available within the country. Nevertheless, you need to burn lots of fossil fuel to produce cement, and there's little coal in Switzerland, so they had to import this. So, concrete as a regional material was a powerful Swiss narrative but one that didn't tell the full truth!

When I began working on the question, everyone knew about the CO2 footprint, but it was not at the same level in the consciousness. However, meanwhile the tone has changed, now it is part of the fundamental decision-making process in design: is it responsible to use this material? Is there a better alternative? It is great that the environmental consequences of the material are in the foreground, but it is just the first step.

And it’s not just visible surfaces, which is often the first thing criticized. Most concrete is used for infrastructure. But are we talking about the concrete in basements? In the structural frame of a building? We need a wider discussion beyond aesthetics and hydropower.

It's cheap. Too cheap. We don't pay enough for it because the environmental cost of the material is not calculated within the price. And it's a global material, but one that is produced locally, not shipped around the world like for instance steel. There is a trend for concentration because larger cement factories can operate more efficiently and help reduce the CO2 intensity of production, although not nearly by the factor we need it to.

The price of the material must reflect the true costs of its use, an environmental tax that reflects the challenges in recycling it. Even crushed concrete recycled as aggregate requires more cement in the mix to make up for the decrease in strength. There are material scientists working on alternative cements that change the process of transforming the limestone. The CO2 that is released is not just from the burning of fossil fuels, but also from the calcination process. Earlier improvements have come from increasing the efficiency of the furnace, but this is not enough.

I do. One of the most powerful things is that in architecture schools every project used to be new construction with little constraints. This radically changed. The ethos of renovation and transformation challenges the idea of autonomy or genius of the architect and suggests that there can be a way of reacting brilliantly to the existing. Does a given site necessarily require demolition? Can we work with what is there instead of defaulting or hoping or wishing for new construction?

Absolutely, and not just by supporting work on alternate materials or encouraging the specification of those. It's also about durability. One major argument is to say that buildings built to last are more sustainable. But this strategy can seriously backfire, if the assessment is not realistic, and robust buildings with high-quality materials end up being demolished after 20 years. The discussion within building culture is sometimes out of sync with the economics of real estate in the cycles of renewal and demolition that impact our urban fabric.

This is part of the discussion that we want to have. The need to consider material choices should not be simplified to concrete being bad, but rather extended to what it means to build in general.

Exactly. There is a Faustian bargain embedded in the act of building, that in order to build you have to destroy. You have to extract, burn fossil fuel, bring in machinery that makes it difficult to preserve the existing. This doesn't negate architecture or infrastructure’s potential for doing good. But it shows the cost of everything that we do. And concrete is just one part of that. Wooden buildings, too, are trapped in the larger ecosystem. Where are your trees are coming from? Who's working on your construction site and what are their labor conditions? What's happening to the material being demolished on the site you're working on? There are a lot of thorny issues. I hope that the discussion about CO2 can work in a more intersectional way, that we understand all the other things that need to be put on the table.